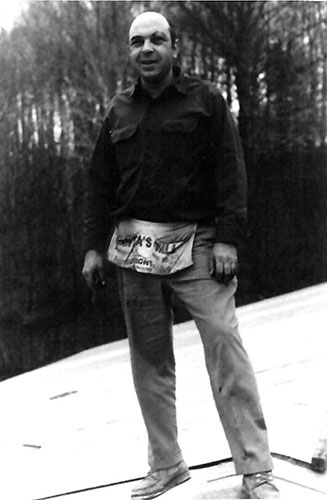

Harry

by Moe Rubenzahl

My brothers and I fell to the ground, rolling in

different directions across the big field behind

the house. My dad laid back, closing his eyes to

the bright summer sun, a stalk of tall grass dangling from his lips. I lay on my stomach, looking at him.

"Well," he said. A peaceful smile crossed his

face. "You've had some questions for me, for a

very long time. Now's your chance."

He was right. There were things I had always wanted to discuss. What was it like to move at

the age of 12 from a noisy, crowded ethnic neighborhood in Brooklyn to

the Catskill mountains with its old, rounded

hills and miles of unpopulated countryside? What were his parents like and how did he

feel when his father erupted with that explosive temper of his? How

did he cope as an only child and primary labor on a chicken farm? And what was it like to grow

up so fast? To lose a mother before graduating high school, be married at the age of 20,

then lose a father two months later? What was it like to hold me, the first of five baby boys?

Were you filled with joy, did you cry? Did you tremble with the weight of raising a family, owning your own farm,

house, and mortgages, and doing it all on your own? Or did you pretend you were not moved

and find some work that needed to be done?

I did not ask any questions. Instead, I woke

up. Since my father's death, I had often thought

of him. This was the first time I had ever seen

him in a dream.

Harry Rubenzahl died in 1986, at the age of 56, the victim of health habits, primarily tobacco.

I did not know it while I was growing up, but my father was an extraordinary human being.

A father at 20 with his own farm, he was a doer. When you're a farmer, you don't call someone

when something breaks or needs to be built —

you do it. If you don't know how, you ask. If

there is no one to ask, you figure it out.

Dad was no Ward Cleaver. In my memory,

he never told us how to be, never sat us down

to explain life. He didn't talk about feelings and

he never explained himself. His way was to address the present and act.

Throughout my childhood, I don't remember my father ever

saying, "I love you." My mother said it all the

time but for the rest of the family, it was unsaid. In later years, I realized that he said it constantly — he said it

when he worked, when he brought something home for us, when he told one of his corny jokes, when he took us

to work with him, when he came home. When I think now of all the fathers who leave their families or who are

never home, I realize just how much my father loved us.

When I think of my father, I always have the

same feeling. There is a thread that connects him

to me, my brothers, our uncles, cousins, and

other men who have carried the name

Rubenzahl. I have never tried to describe or explore the feeling but I know there have been

moments with my brothers when we all felt it.

Some years ago, my brothers and I converged

on the house where we were raised to give it a

new roof. We were all there, pounding nails in

the screaming August heat, slapping down

shingles and slamming down beers, the sweat

coming so fast that we never wiped it away, it

just dripped off our chins onto the next shingle.

As we worked in silence, I think it was Marty,

the second oldest, who first noticed the sound.

We were all whistling to ourselves. It's a quiet,

breathy whistle that comes from tongue and

teeth, following absolutely no recognizable tune.

I don't recall how, but we all suddenly became

aware of the four meandering melodies and began to laugh. We didn't discuss it but we all

thought about where the habit had come from.

There were hundreds of people at Harry

Rubenzahl's funeral. It was a bitter cold January day in upstate New York. Not a day to be

out. But many people loved and respected my

father and had to come pay their respects.

The focus was on his bride. Everyone wanted

to make sure she would be all right. Marion was

a teenager when they were married, a mother a

year later. These two people had never lived

alone. I remember the tight circle my brothers

and I formed around her, holding her and protecting her from the cold. Four sturdy sons, her

boys. Everyone knew how strong she was and

we all knew she would get by. But how? This

was too much pain. She would not use the term

"widow" for two years.

It is amazing to me how often I think of my

Dad. Even now, eight years later, he enters my

thoughts at least once a week. When I look in

the mirror, I see his committed brown eyes and

the two crooked front bottom teeth. When I talk

to Arty, who lives with my mother in the home

I first saw two days after my birth, I hear it as

he shrugs off a worry using Dad's "eh!" When I

think of Marty, so fiercely independent he lives

in Puerto Rico. When the youngest, Murray,

swings a hammer, nails hanging from the corner of his mouth, intently working, working,

working, I see our father.

Mom still lives in the same house in upstate

New York. My brother Arty lives there too. He

takes care of the place, grows a garden. Things

are different there. Different people, new

kitchen. The old chicken coops are gone. She

does all kinds of things Dad used to do — manages the finances, gets the driveway plowed,

orders heating oil. Somehow, she manages to

get things off the high shelves. She has started

her own business. She even has a boyfriend or two.

But no matter how much things change,

Harry's presence remains. It's in everything. Not

just the furniture and the house and other tracks

he left in his path, but in the deeper things — in

the personalities, habits, and memories of those

he left behind.

I will never get over my father's death. It will

never be history for me. I really miss him. Yet

there is a sense that he is still around.

Many men I know have lost their fathers.

There are a few life experiences that can not be

communicated — birth, love, loss. Justin Sterling said a father's death is the biggest event of

a man's life, bigger even than the birth of a son.

Most men will experience it.

When a man I know loses his father, there is

nothing to say. I just let him know I have been

there, too. But I want to tell him much more. I

want to tell him I know how he feels. I want to

tell him no, you will never get over this. Yes,

you will always miss him. You will always wish

he was still there, making dumb jokes, embarrassing you with his old habits, doing everything his way, even when another way seems

better to you. You will continue to see him in

the mirror, you will keep seeing his tracks in

the lives of those around you.

My father is my first and greatest hero. The

things he gave me are immortal. I like to think

that makes him immortal too.